Radio was the original overhyped technology

The tech hype cycle started a century ago.

It was a plaything for the wealthy, a tool for the powerful, hailed as a democratic gift to humanity.

It was geeky, technical, jargonistic. You’d debate the merits of the smallest changes, remix and reinvent, preorder the latest take months in advance, then watch the shipping date slip further into the future.

It spurred innovators to greatness and grandiose. “There are no imaginable limits to our opportunities,” a government commissioner would enthuse.” “I aim at Tesla,” said the self-styled father of this new technology.

It would bring the best of times; nothing else could possibly “touch the lives of all people more intimately,” as one put it. It’d also bring the worst of times; it could “suppress and distort fact,” even “stir up mob violence,” another worried.

We were promised driverless vehicles a century ago, and all we got was the radio.

Into the ether

It started out as a spark. We’d tamed lightening, as our ancestors had tamed fire. We’d brightened the darkness, built the first automobiles, sent messages on wires coast to coast.

“Do you think there is a limit to the possibility of electricity?” Thomas Edison was asked in 1896. “No,” replied Edison, “I do not.”

Edison then fretted that the next innovations might not surprise us; “Nothing now seems to be too great for the people to comprehend.”

He needn’t have worried. “Tesla foretold of a day,” Thomas S. W. Lewis wrote of Edison’s archrival, “the seemingly magic electrons would enable messages and sounds to be send across great distances without wires.” That’d spark the next generation of innovations, kick off a tech cycle that’d transform the world—or so they dreamed.

It started out with wireless Twitter—or rather, with Guglielmo Marconi’s wireless telegraph, sold first to the British Navy in 1897, then used in 1899 to report on international yacht races. “The possibilities of wireless radiations are enormous,” said Marconi to a reporter. Then he started the first wireless company, sent a transatlantic message through the air two years later.

And the race was on.

Tinker, transmitter

First came ego and eccentrics. “Some days I don’t sleep,” Edison would claim when asked about his work/life balance. “I must be brilliant, win fame,” wrote Lee de Forest, the self-styled father of radio, in his journal. “I aim at Tesla.”

But maybe it takes the crazy ones. You can’t just invent the future; you have to sell it, too. Marconi was ready for both, with “the vision to harness the discoveries of others” and add a few of his own, combined that with “the skill of a P.T Barnum” to promote the ideas.

So you’d try crazy things until something worked. Marconi “absently placed one part of his aerial on the ground while holding the other part in the air,” and voilà, antennae would live on roofs for the following century.

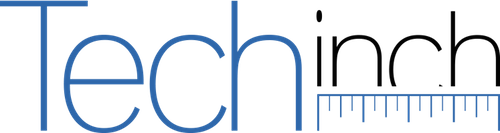

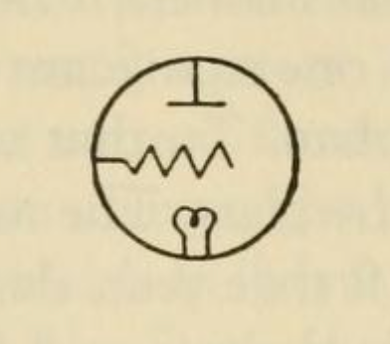

You’d remix. Edison discovered the “Edison effect” as carbon passed from a lightbulb’s filament to the glass bulb, John Fleming turned that into the diode, then de Forest perfected it with a battery, circuit, and zig-zagged nickel wire to amplify the radio signal with his audion—an early take on the triode that lives on today in high-end amps.

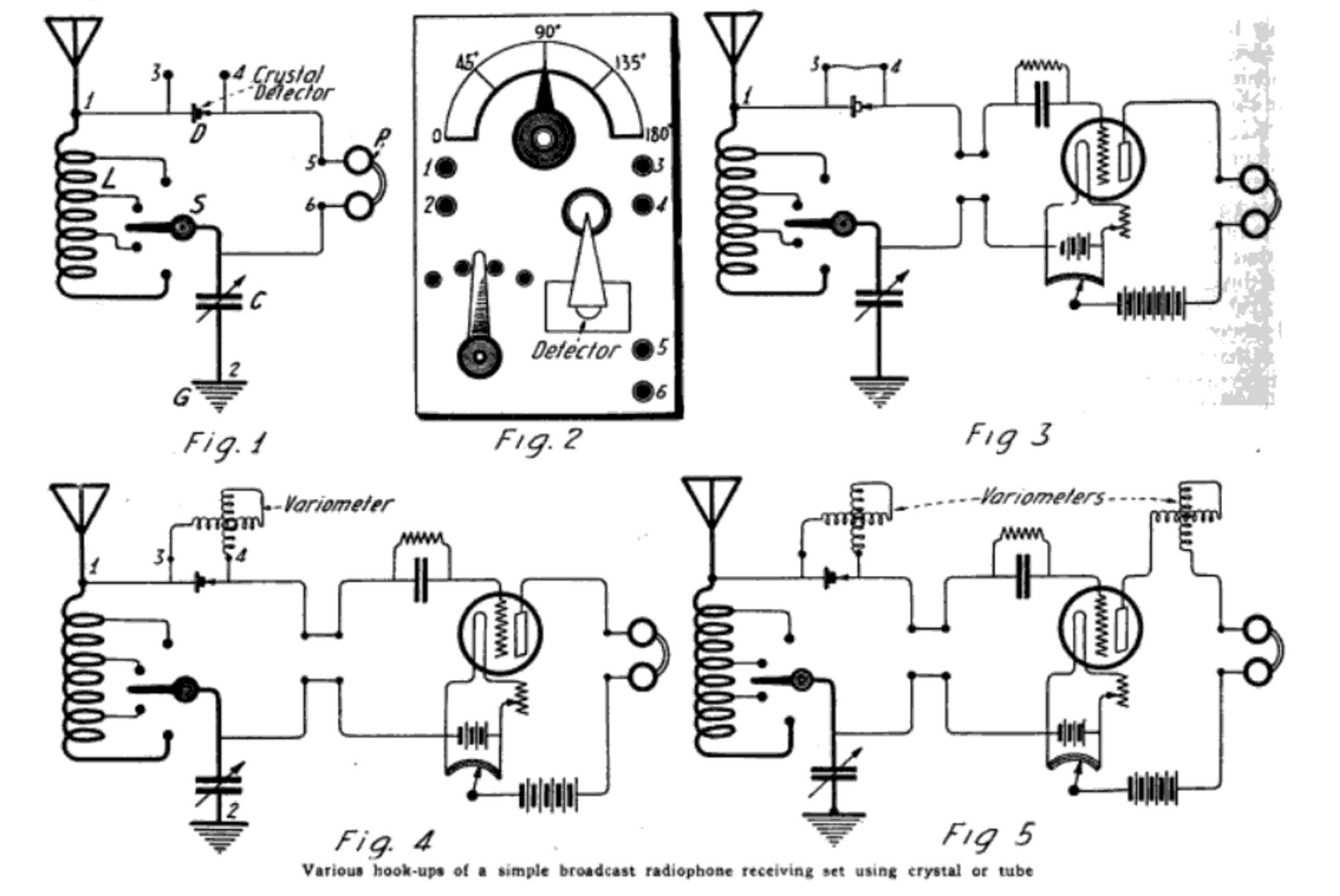

It was geeky, a hacker’s paradise of parts and schematics, a new frontier where you could broadcast your ideas. You had to learn new science, of intercepting the signal, tuning into a broadcast, and amplifying the audio to hear it. It wasn’t for everyone; it was for those who took the time to obsess over the smallest details in journals like The Phonoscope, Wireless Age, and Radio Annual.

It was eccentric, the next big thing.

The hopes and fears of all the years

And then radio was everywhere, the new thing everyone couldn’t get enough of. “Soon the human ear and imagination became insatiable,” wrote Lewis of the radio. “People wanted more of everything—music, talk, advice, drama.”

It’d rescue you, from shipwreck and snowstorm, fire and flood. It’d educate; “There are no imaginable limits to our opportunities,” enthused the US Commissioner of Education J.W. Studebaker.

It promised a driverless future, even. “Steer a ship from a distance?” repeated New York Herald reporter to Guglielmo Marconi, after his comment about the potential of the wireless telegraph. “Certainly.”

And yet, the dreams were paired with anxiety. Governments imagined radio’s potential for spying; citizens worried it could tell their darkest secrets. “It’s going to be embarrassing if the collection agencies start a broadcasting station” and broadcast the names of debtors, a letter to the New York Telegram imagined.

Radio, indeed, could threaten everything. It could “threaten our whole telephone system, I may add, our whole newspaper system,” theorized a chief Marconi engineer.

Fake news became the new worry. Radio “can inform accurately and so lead sound public opinion; or it can suppress and distort fact and so grossly mislead its hearers,” wrote National Broadcasting Co.’s Dr. James Angell in 1939. “It can stir up mob excitement, even to the point of violence,” he said without citation.

Freedom itself was in question. “Radio, in a democracy, is of tremendous importance, of far larger importance than we yet realize,” wrote H.V. Kaltenborn in the same publication. And so, National Broadcasting’s Angell teased out the question: Should radio be “controlled by the rulers,” or should it be free, or free but with the oversight that it is “never abused?”

Even equipment came up for debate. Should ships rent radios, or buy them? “The French pride possession,” a debater argued, while “In this country we get better service and better terms by rending our telephones,” debates that echo those over smartphone subsidies a century later.

We’d gone from wires to wireless in a couple decades, from debating how to build the best radio to how it should be used. Frequencies and filaments took a backseat to policy and practice.

And just as quickly, it faded into the background as just another part of life—important, a new part of the fabric of society, even, yet hardly as consequential as was once imagined.

It was just the radio, after all.

I am for peace, but when I speak…

There’s something deeply human about overestimating the change new technology will bring.

“In the future there need be no disputed readings, no doubtful interpretation of text or delivery,” wrote The Phonoscope’s inaugural edition in 1896. “Death has lost some of its sting since we are able to forever retain the voices of the dead.”

And that was for the phonograph, with voices etched in resin.

Radio elicited loftier ideas. de Forest was driven by visions of a utopia, one with “no war … easy & rapid & cheap transit.” Tesla, at a Radio Institute dinner in 1915 on the eve of World War I, hoped that “wireless would prove an agent of peace in binding the nations closer together,” even as the gathering included “many nationalities, notably those of belligerent countries.” even as Marconi—the inventor of wireless telegraphs—had arrived to New York for the event aboard the Lusitania.

13 days later, the illusion shattered, as a German U-boat’s torpedo sank the Lusitania and brought American into the war. Soon the United States would be recruiting radio operators, adding Radioman as a new rank in the Navy.

The tide of the Great War, nay history, was turned on the airwaves. Peace would come, but would have to be battle-tested first.

And then we’d dream again. Even before the dust settled, the 1918’s Radio Telephony textbook was dedicated to radio as the “promoter of mutual acquaintance, of peace and good will among men and nations.” The dream of technology changing the world would live on.

Lasting peace proved elusive, technology regardless. War or the rumor thereof, if anything, provided the spark and sponsorship to push technology forward.

Then came the computer, to crack wartime codes and calculate where bombs would burst and tabulate first the government then the international business world’s data. Then came rockets and the space race, ostensibly to put a man on the moon—or a missile on your foe. Then came the semiconductor, to fuel that space race, then be the brains behind the software that would eat the world.

And once again, we’d decry the the privacy implications of the latest technology, puzzle the geopolitical ramifications of who owns and who copies the technology, worry it was ruining everything. And we’d dream again that it’d be the end all, cure everything, bring the world together, make our self-driving vehicles actually happen this time. It’d bring out the best and worst of us.

And perhaps, like radio, decades later it’d be just a thing, a bit of nostalgia, something that got us through our days, something that occasionally made everything better and other times made everything worse.

It’d be like everything else humans make. Soon enough, we’d move on to the next greatest thing.

Originally published on the now-defunct Racket blog on August 5, 2021. Tree photo by Fabrice Villard via Unsplash. Radio photo by Markus Spiske via Unsplash

Thoughts? @reply me on Twitter.